Language Is Not An Empty Vessel

How the logics of power and abuse utilize language to justify violences

Today, I am in the sun, trying to find words. This time of the year holds death in it. Death–which Western society looks away from, fears, and abhors. What are years of life–and the wisdom that this brings–worth in a society which seeks truth in only carefully curated forms? What is the weight of wisdom?

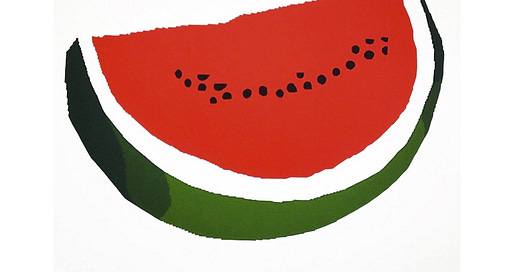

I look at images of death on my screen. We witness Palestinians being tormented–their land destroyed, homes bombed, hospitals invaded. The people are being subjected to such horrible violences that have grown out of years of violent occupation, surveillance, and destruction. The land, and the inhabitants of it, are screaming.

In my head, I keep repeating: This is the climate change plan–at least for state powers. Increased militarization, more wars, more hoarding of resources, more treating people as disposable, more genocide. Where is the investment in care, in compassion, in systems which work for all of us?

In a 2005 image by Jaafar Ashtiyeh, 60 year old Palestinian woman Mahfoza Oude, cries and hugs an olive tree in the West Bank. On social media, someone comments, “This is the whole crisis summed into a photo.” (Apologies for lack of credit–it’s stuck in my head, but I cannot find the comment anymore.) One does not need to be a political theorist to recognize a land grab. One does not need to have read too deep into history to recognize patterns.

On the phone, I try to refute the comments a loved one says to justify these violences. They ask me, The land you’re on is stolen. Why don’t you give it back? This was offered as a rebuttal to me saying, I will never support war or genocide. A week later, I am still sitting with these words, wondering what power they held to them, and why this was seen as a pointed response, a winning remark, to me saying clearly, I do not support genocide.

I have heard this statement before as a response to anyone expressing compassion for the Palestinian people. Someone is proliferating this line of thinking. I believe its intention is to say: Look, your words are empty. Your actions are performative. Or, justly, What about honoring the Indigenous peoples where you live?

But to me, these words do not hold weight in justifying genocide, or trying to quiet anyone who may speak up against it. In fact, they seem to do the opposite for me. They are a recognition of the interconnectedness of struggles. One does not need to study history for decades to see how the destruction of the land is related to colonialism, racism, class, gender, and all forms of oppression. The Palestinian movement is a Land back movement. This is not separated from struggles for land and Indigenous sovereignty, wherever they may be occurring. On Sunday in Amsterdam, after being interrupted by a protest disruptor, Greta Thunberg led protestors in the chant, “No climate justice on occupied land.”

I do not know that it is productive, or necessary, to get into the weeds of discussions. I see the clinging to a stance, and the desire to stand by the State no matter what may occur. I see the seemingly endless bag of excuses and logic, with a new rebuttal being pulled out each time the same words are reiterated: I do not stand with genocide. I want people to not be bombed, to have food and water, to not be murdered. I want the land to not be destroyed.

I see how the logic of power utilizes the logic of abuse–how they are one and the same. I have experienced the logic of abuse. I have heard the mental gynamstics, and experienced people pulling justifications from a long bag as I tried to name my experiences. I have felt crazy. I have questioned whether I really experienced what I did. I have been told I am overly sensitive, naive, a baby, and making a big deal of nothing when I tell others that they caused me harm. I have been told to let go of the past when I bring up unresolved experiences of harm. I have been offered justifications. I have been told that perhaps I deserved it. And, in moments of breakthrough, when the events are clearly before us, I have been offered a quick apology, then asked if we can move on now. I have also been told, That never happened.

Years of this sort of dialoguing has made me invested in, and deeply curious, about the way language is used to justify abuses. It has made me listen very closely to language, to read, educate myself, and write my experiences down as clearly as I could. Am I a writer because I needed to remember my own experiences in light of being discredited? Or am I simply a writer who has used words to speak on what was around me?

I see the power in words. Language is not an empty vessel. It is a carrier of history, and what we say holds weight. Language archives time–it holds it in every word. What we say, what is repeated over and over, eventually becomes what is remembered. The way a story is told gets passed down through generations. Cultural memory lives on through language.

my archive, your archive, our archive. . . . archives of ownership, of reclamation, of record, of discovery, of yourself in a strange land by the still or turmoil waters where you lay down weep, where you lay down and dream, where you become free. - poet Kamau Brathwaite, Black Writers Conference 2010

Power, in all its forms, knows the importance of shaping language. Systems of power knows that they need to control the narrative to be able to hold onto power. Language can be a tool for desensitizing people to others’ pain, just as much as it can be a tool for deepening sensitivity. The language of dehumanization obeing spread right now says that the Palestinian people are animals. On October 9th, 2023, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant stated: “We are fighting against human animals.”

In a 2021 Psyche article titled “What our use of animal-based slurs and endearments says about us,” the writer and professor David Egan wrote,

“When we invoke animals to demean our fellow humans, we also thereby reinforce an underlying conception of animals as contemptible. In most areas of dense human settlement, wild predators have been hunted to extinction. Most livestock live out a short existence in conditions so hellish that agricultural lobbies have pushed for so-called ‘ag-gag’ laws that criminalise their documentation. Rodents and many other liminal animals are exterminated remorselessly.

In ways both obvious and subtle, our language desensitises us to this cruelty.”

The language of power has long likened humans to animals as a way to justify, and desensitize people to cruelty. It appears to be a favorite justification of cruelty. Perhaps this is because–devastatingly–it continues to be so effective.

On NPR’s “Talk of a Nation” in 2011, David Livingstone Smith discussed the psychology of cruelty. A write up of the episode began,

“During the Holocaust, Nazis referred to Jews as rats. Hutus involved in the Rwanda genocide called Tutsis cockroaches. Slave owners throughout history considered slaves subhuman animals. In Less Than Human, David Livingstone Smith argues that it's important to define and describe dehumanization, because it's what opens the door for cruelty and genocide.”

The write up continues: "We all know, despite what we see in the movies," Smith tells NPR's Neal Conan, "that it's very difficult, psychologically, to kill another human being up close and in cold blood, or to inflict atrocities on them." So, when it does happen, it can be helpful to understand what it is that allows human beings "to overcome the very deep and natural inhibitions they have against treating other people like game animals or vermin or dangerous predators."

Finally, Smith states, "When people dehumanize others, they actually conceive of them as subhuman creatures…as they can then "exclude the target of aggression from the moral community."

This logic of cruelty, dehumanization, likening people to animals, and finding ways to control the narrative in order to justify violence is not new. I question how, and why why why, people are able to hear other human beings likened to animals, and not pause. Why they do not think very critically about what they are hearing. Have they not heard this before? Do they not listen critically to propaganda and wonder what work it is trying to do on them? Do they not question why being called an animal justifies any violence to begin with? Do they not see that no being deserves violence being inflicted against them? I question why someone in my life that loves animals then spits out that Palestinians human animals as a response to why they believe the violence against them is justified.

But I also know how persuading the logic of abuse can be. I see how people cling to it in order to cling to power, or their perspective. I know how people’s grief, fear, and anger is played upon in order to sell them a narrative.

I see how afraid people are of losing their versions of reality, and of seeing things as they are. I see how people cling to their pain, and do anything to avoid feeling the entirety of it–even utilizing the same language of cruelty, and inflicting the same cruelty that they experienced onto others.

I see how we would rather continue as “normal” than have to change our behaviors. In my own life, I have experienced how seeing things as they are and how recognizing abuse for what it is–in all forms–has made it impossible to continue as usual. I also have seen no other way but to be changed.

I see how much of a privilege it is to be able to ignore what it taking place. I see how a heart can harden. I see how a heart can become so desensitized that it no longer feels compassion, even when it looks. I see how a hardened heart can look, but no longer see.

In the 2017 essay, “searching for a new kind of optimism,” from the book They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (and published on MTV here) writer Hanif Abqurraqib wrote, “...I’m not as interested in getting things better as I am in getting things honest.”

He went on to write,

“I’m not sold on pessimism as the new option. I need something that allows us to hope for something greater while confronting the mess of whatever all this blind hopefulness has driven us to. America is not what people thought it was before, even for those of us who were already familiar with some of its many flaws. What good is endless hope in a country that never runs out of ways to drain you of it? What does it mean to claim that a president is not your own as he pushes the lives of those you love closer to the brink? What is it to avoid acknowledging the target but still come, ready, to the resistance?”

I’m not sold on pessimism either, nor am I sold on the disregard of anything which may deemed too heavy to hold. I am here, parsing through language, as I have been doing for years to understand my own life. I am looking for patterns in order to understand what is being sold to me, and why. I am digging into my own heart because I know that my attention, that all of our attention, holds weight.

I am building and attending to language the best I can. I have seen how it is a tool for oppression and desensitization of violence. I have seen how it is used against others. I have seen how it has been used against me.

And because of that, I also see the importance of archiving and writing as ways of setting the record straight, as well as looking for ways outside of cruelty.

In a 2000 essay in Essence magazine, Octavia E. Butler wrote about predicting the future. She wrote,

“So do you really believe that in the future we’re going to have the kind of trouble you write about in your books?” a student asked me as I was signing books after a talk. The young man was referring to the troubles I’d described in Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, novels that take place in a near future of increasing drug addiction and illiteracy, marked by the popularity of prisons and the unpopularity of public schools, the vast and growing gap between the rich and everyone else, and the whole nasty family of problems brought on by global warming.

“I didn’t make up the problems,” I pointed out. ‘All I did was look around at the problems we’re neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters.’

“Okay,” the young man challenged. “So what’s the answer?”

“There isn’t one,” I told him.

“No answer? You mean we’re just doomed?” He smiled as though he thought this might be a joke.

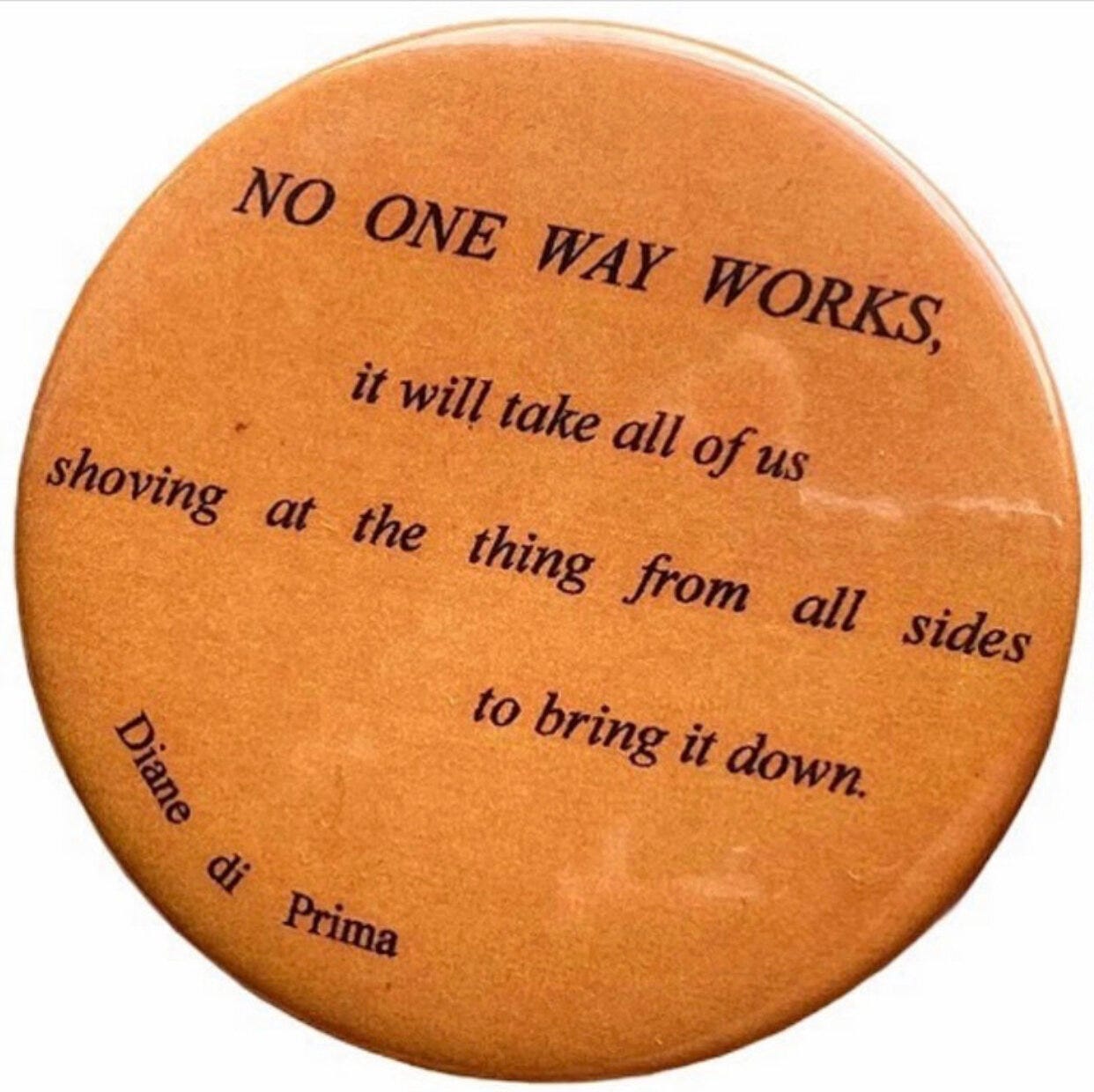

“No,” I said. “I mean there’s no single answer that will solve all of our future problems. There’s no magic bullet. Instead there are thousands of answers–at least. You can be one of them if you choose to be.”

May we change our lives, in big and small ways and find ways to resist power, forever.

I’m sending you all love and solidarity,

Lora

Some ways to shove at this thing from all sides:

If you’re in the U.S., 5Calls makes it easy to call your representatives, and ask them to support a ceasefire. While I understand the resistant to electoral politics (and really, the deep and rightful distrust and disillusionment), this holds eight in stopping the government’s funding of this violence.

Jewish Voice for Peace has several actions listed on their website, including calling upon President Biden and congress to ask for a ceasefire, and demanding better coverage of Gaza in the New York Times.

CAIR Know Your Rights guides—as a student, employee, while traveling, with the FBI/Law Enforcement

Know Your Rights as a protestor by the ACLU

Learn about Atlanta’s Cop City, and its connections to Palestine. Actions against the destruction of the Weelaunee Forest are taking place right now.

Please comment with any other ways if you so desire. This can be interrelated to various struggles, personal or collective, big or small.

Thank you for writing this. I needed it.