The table is set with purple crêpe paper. It crinkles as hands move white ceramic dishes over it. Cool natural light slips in from an unseen window. A hollowed out grapefruit rests in the table’s center. Near it, a bowl of bright red, tightly packed raspberries with green mint leaves sprinkled on top. A plastic Tupperware sits open with deep burgundy cherries in it. Two roses rest on top of the cherries—one white, the other red. Their long, thorny stems signal that this is not simply a view into a meal, but a staging, a photographic performance.

The scene is a photograph by German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, from his Still Life series. The series often depicts simple moments. One image shows green plastic bags collecting dust on a windowsill. In another, smooth white rocks are positioned beside two potatoes. They sit atop gray denim whose wrinkles produce deep shadows. When printed, the rocks and potatoes are blown up to enormous proportions. I imagine the rocks at their original size being slipped into a pocket, and a finger brushing over them behind the enclosure of fabric. I imagine a hand running over the bumps of the potatoes and wiping the soil from them. On the blank white wall of a gallery they are made monumental. They radiate out of the thin white frame.

These images feel familiar. Food is on the table. A meal is in the process of being eaten. Soon there will be cleaning to do. Someone will have to collect the dishes from the purple crepe paper, squeeze soap onto a sponge, run water over the plates, wipe them dry, then put them away. Mundane, everyday action is shown in these photos, and yet, they are staged. The photographer’s hand is present in the arrangement of the objects. They are looking down on the scene, and deciding how to tell the story.

Last semester, I took a poetry workshop course. The professor, C.S. Giscombe often urged us to record what we saw without trying to find meaning in it. Sitting around a wooden table in a stuffy room in Wheeler Hall, nine of us listened as Giscombe quoted T.S. Eliot. Eliot called poetry a “burglary” and asserted that meaning is not the important part of a poem. Rather, meaning is meant to “satisfy one habit of the reader, to keep his mind diverted and quiet, while the poem does its work upon him: much as the imaginary burglar is always provided with a nice piece of meat for the house-dog.” Giscombe concluded that how a poem feels is much more important than what it means.

A few days ago, Pedro and I were at Lake Merritt, sitting on damp grass with our notebooks open on our laps. We had befriended each other in Giscombe’s class. Now, we had a habit of meeting up to share coffee or deli sandwiches and do writing exercises together. This week we were field noting what we saw around us. While a 30 minute timer counted down on Pedro’s phone, we looked around and took notes.

Downturned face chewing gum. “It was like swinging a pick ax.” Riding with no hands. “I’m still in love, with youuuu, boy.” Every streetlight I can see is red. Red tinted ice in a plastic up, lifted and deposited into a mouth. Red chipped nail polish with dirt under the nails. A gull with someplace to go. White bike rims steered down a dirt path by a rider wearing all purple. Music pouring out of a speaker attached to the bike streams down the lake. Boom clap boom clamp boom. A sneeze is thrown into a fist. Overhead, one gull has chosen to go high. Steadily, an all white airplane moves forward. The geese are on their way and scream for all to know. Am I afraid of just looking? Am I afraid to take my pen off the page?

When the phone timer sounded, Pedro and I chatted about our experiences of looking and recording. Despite my two notebook pages full of notes, I felt I had nothing to say. “Well, Giscombe would say that’s the best stuff,” Pedro responded. “The banal,” they emphasized.

The Oxford dictionary defines banal as “so lacking in originality as to be obvious and boring.” But observing banality shows me how much I do not notice what surrounds me. It points me to new connections. How challenging it can feel to describe the feeling of being in life. As the U.S. poet Stanley Kunitz said, “I dream of an art so transparent that you can look through and see the world.”

One of my clearest memories from childhood comes from when I was 13 years old. My mom, brother and I were spending the summer outside of Montréal. This was a habitual summer setting for me. My mother grew up in Montréal, and it was normal for my siblings and I to spend summer there visiting her parents. Usually, we stayed in her parents home, but this summer we were in a nearly empty house in St. Lazare. There was no furniture in the house–no fridge, no oven or stove. We slept on air mattresses in separate bedrooms and stored perishables in a neighbor’s fridge. Our visit was focused on visiting my mother’s dad, who was hospitalized with cancer. We would travel south towards the city, until we reached the large red brick hospital. There, we would repeat our names to him in the quiet blank room he slept in, watching as he grew thinner.

But the memory I have is smaller than this. It was August and I was sitting on the front steps of the St. Lazare home. The air was humid and thick. I had my journal open in my lap, and every so often, I’d look down to scribble something. The handful of other kids who lived close by were on their bikes, doing laps around the neighborhood. My brother had been invited to join them, but I hadn’t. I wanted to be in the group of bikers, pumping my legs over my pedals in the dwindling sunlight. I wanted to feel the sensation of biking fast and steering myself quickly around street corners. Instead, I was looking around, noting what I saw, and writing it down.

As a teenager, I clung to the idea of being an observer. It was a role which gave me solace. So what if I felt shut out from others around me? So what if I felt misunderstood and lonely? It didn’t matter that the neighborhood kids didn’t want to bike around with me. Or that my brother broke our thin wheeled road bikes by jumping off handmade dirt jumps. It didn’t matter that the bikes had formerly been my grandfather’s and were some of the last things we had from him. Or that my grandfather passed away before the air turned cool and crisp. Or that my family decided to stay in Quebec, and I started at a new high school where I didn’t know anyone. Through writing, I could submerge into my own world, and live inside what I felt and saw.

Now, I find it a bit strange to take pride in observing when it is something we all do. I wonder, what kind of person brands themselves as an observer? What kind of person am I? And further, is it possible to simply observe? I look at the world from my own perspective. Whatever I see has myself in it.

Last fall, on a field trip with Giscombe’s poetry course, our small class traveled to Elkhorn Slough near Monterey. We were there to field note and later, build a poem from our observations. Moving down the hard dirt path in search of the shore, we pointed out the bright green witch’s hair blowing on gnarled tree trunks. On worn down railroad tracks, we crossed quickly, and were greeted with the scent of fresh thyme. Looking out at sawed down trees, my classmate Clayton said aloud, “We can’t look at anything without ourselves in it.” When I returned home, I wrote a prose poem about the long, warm day. Clayton’s comment jumped across my observations. I noted, “Here I am, in it, intruding..” There is no objective looking. Everything I do is clouded by my own perceptions.

Months later, I am again thinking about advice Giscombe gave our class. He noted that often the most interesting things are what one did not mean to stumble upon. As with most advice, my understanding of this statement has expanded beyond when I first heard it. Looking around for a bit longer than usual can interrupt a habit of quickly coming to conclusions. Perhaps, if the subjectivity of looking is recognized, it can interrupt ideas of truth as a singular experience. If I recognize my own subjectivity, can I complicate my own idea of truth? Can I allow truth to splinter into other possibilities?

I want to preserve what it feels like to live life, to look at it, to love it. I want to archive the sound of my friends’ laughter around a wooden table, while the moon rises above us. I want to hold onto the feeling of magnolia flowers blooming outside my bedroom window in Oakland. I want to make things that remind me to look deeper, and to keep looking beyond the point of thinking I’ve understood. In the essay On Joy, the poet and writer Hanif Willis-Adurraqib wrote,

“I realized this urgency to archive the things that are not promised. I need the joy in my life to live outside of my body. I need to see it, to touch it. I need that outside of my body even more than I need the rage, confusion, and sadness on the outside. I know the sadness will always replenish itself. There is no certainty in almost anything else….Surely, each small joy has an expiration date. I have touched the edges of them. I don’t know how to fight against this reality except for to write into these moments with urgency. With fearlessness and hunger.”

In 2017, I learned firsthand that my friends were subject to irreconcilable changes. My ex and close friend was in an accident that left him with a traumatic brain injury, paralyzed from the waist down, and in a coma for over a year. After the initial shock of grief settled, I did not know how to write about the ways life changed. But I felt, with new urgency, the weight of Adurraqib’s words.

Soon after the accident occurred, I flipped through my notebooks, looking for writing which preserved images of my friend. I searched through online image archives I had and my phone photo library. I wanted to find ways to make memory more pronounced.

Three years after the accident, I found myself employed in the role of part-time caregiver for my friend. It was 2020 and the pandemic was raging on. Several times a week, I drove down the 94 East freeway to my friend’s dad’s house in East county San Diego. There I would cook my friend lunch, crush his pills, and drive him to appointments. Life had changed irrevocably. Memories which I had originally wanted to pull out and make tangible were now embedded in my daily routine. The past had presented itself to me not as a finality, but as changeable. Several months into caregiving, I wrote a poem titled “Somehow It Returns”:

The thing I was out looking for, what I thought was lost and irrecoverableI found it plainly– while chopping mushrooms in your dad’s kitchen, waiting for the oil to heat behind me I was making our lunch, and you called to me from the next room, asking for a glass of water There is loss, but there is renewal too I hand you the glass, drop some garlic into the pan Once you were my partner, now you are my friend Once you cooked me lasagna while I was sick from my own head Now I bring you crushed acetamphoenin and tacos What I thought I lost irrecoverably has come back so quietly and plainly that I wonder if it ever left

The past seems to change with context. When I was caregiving for my friend, a friend who had once been my partner, past experiences took on new layers. I no longer reflected on our romantic relationship ending as the final point in our relationship. Instead, I stood in his dad’s kitchen, chopping mushrooms, and felt how time had folded itself into a new shape. Memory was not a closed narrative. All my photographic and writing archives from the past years were not closed. They had the potential to shift and to come alive under new, unexpected changes.

Over the years, pictures I took on my phone have become backdrops for fake film stills. Lines from my phone’s note app have been inscribed over photographs. Through this process of collaging, linear timelines have been interrupted. Recontextualizing writing and images is exciting to me. By interrupting a sense of linearity, I am able to piece together a timeline on my own terms. I can recognize the past as alive and make new connections from it.

In a photograph I took on my phone in 2019, a hotel entrance in Utah lives on. It was July and (another) ex and I were on a road trip. It was only day two of this trip, but we were already having car trouble. After a warning light had turned on his dashboard, we’d booked a nearby hotel and left our tent in the back of his silver Camry. I took the photo the next morning, while an AAA worker went over potential options with him. Some part on the car needed to be replaced. We would likely have to go to a nearby garage to get it fixed. The sun was rising and already it was pushing 85 degrees.

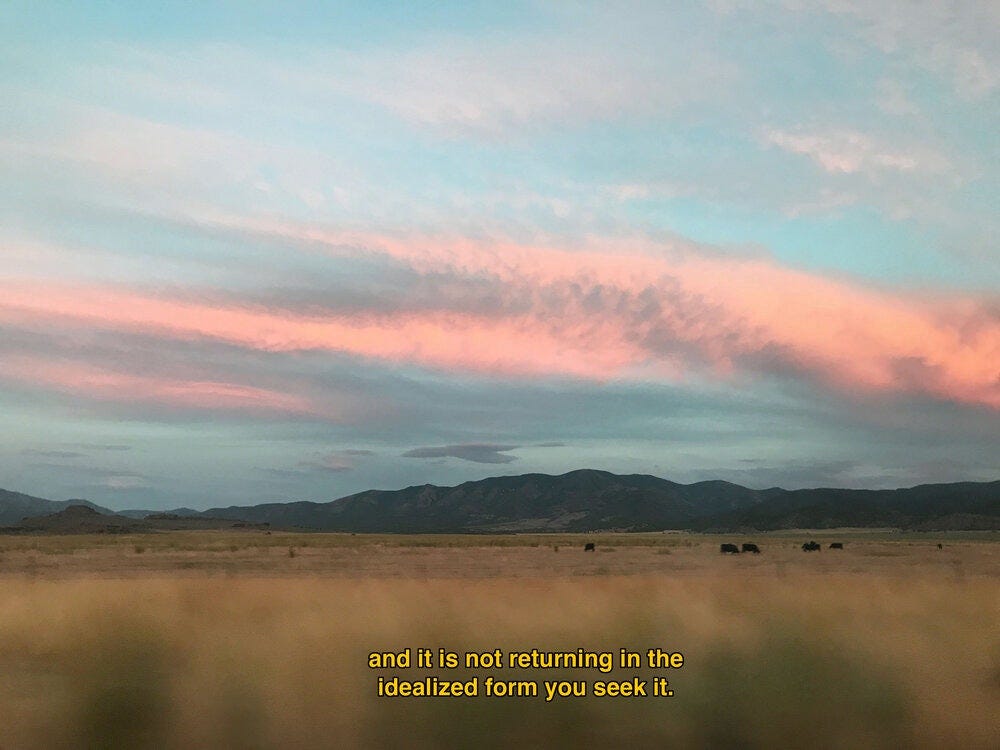

A photo I took the day before this scene shows a pink sky and cows in the distance. It is blurry and signals movement. I took the photo from the passenger seat of my ex’s car minutes before his check engine light went on. Months after he and I broke up, I inscribed text onto the photos. Words complicated the meanings behind them. “The past is a fiction you wrote,” the first photo reads. The second finishes the thought, “and it is not returning in the idealized form you seek it.”

These were no longer souvenirs of a trip to Montana and Wyoming, but objects which had shifted with context. Their linear timeline was disrupted.

Disrupting a linear, unilateral timeline within art making, helps me acknowledge truth as multi-faceted. I did not take those photos intending to use them in this manner. Nor did I know that several months after my finger had pressed the shutter, I would no longer be dating the person I had taken the road trip with. The images expanded beyond their original function as roadtrip souvenirs, into articles of complicated memory.

Sometimes after I’ve read my poems to a roomful of people, strangers have approached me with a bag of questions. “Are your poems about real events?,” they inquire. Once, in an L.A. living room, a stranger asked, “Did you really lie in the middle of the street and call it therapy?” I was standing in a small group of strangers, making small talk when the question came. Though I can’t remember how I exactly responded, I do remember being embarrassed while answering. Now I question if a nonlinear presentation of lived experience is still true. If I laid in the street but did not say aloud that it was therapy, is the poem true? Are collaged details true? Are feelings truth?

In the summer of 2021 I moved to Oakland and spent my first few months in the city doing a class on Zoom. To fulfill an assignment for an online photo class I was taking, I photographed details of my life. In a self-portrait, I am cutting my bangs in my bathroom and bits of brown hair are littered over my face. In another image, groceries tumble out of a brown paper bag and spill onto the wooden table in my kitchen. Another photo shows a half smoked joint lying in an abalone shell. An Oakland parking ticket and cassette tape I found on the street are beside it. All of these images were staged. In the self-portrait, I am holding my camera in one hand. In the other I was lifting scissors to my bangs and snipping. The groceries pouring out of the bag had been carefully arranged. So too had the parking ticket, cassette, and joint. Yet they are all consistent details of my life. Are they true?

The word “artist” is loaded with implications and expectations. Many times, the artist is described as one who can lead us to truth, point out what is profound, and offer understanding. But I’m more interested in finding the presumed lines between life and performance, and playing on the boundaries of each. As Anne said to me in our Zoom meeting about this project, ‘“I’ is a pronoun too.” The self can be a performance and an invention.

I would like to contain life in a neat, ordered format. To tuck it into my journals and have it remain forever as I once knew it. Maybe then I could have a concrete sense of understanding. My friends could remain forever in the ways I once knew them. Then the past could be preservable, and a solid footing of truth could be found.

But remembering has shown me it does not follow a cohesive timeline. Traumatic moments have surged back into me with forcefulness. They have shown me that memory lives on in the body, even when I think I’m “past” it. And time has shown me that my relationship to anything can change. I assert that I am one way, then surprise myself by acting in another. I believe I understand something, and then it is complicated by new questions.

In the album Microphones in 2020, singer Phil Elverum sang, "Anyway every song I’ve ever sung is about the same thing: standing on the ground looking around, basically."

Perhaps this is what I can hang onto. Truth and linearity may resist easy definition. When I believe them fixed, they may reveal new layers of themselves. But I can look around and note what is there at that moment. Again I can be surprised when unexpected connections surface. I can acknowledge my own subjectivity, and my performance of an “I” that is deepening and unraveling. And perhaps I can have some fun with it. Perhaps here, I can strut across the stage and take a bow.

incredible, thank you. after a first reading, I want to sit with this feeling, but I'm excited to return for a second read and delve deeper.